Shah Jahan

| Shah Jahan I | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sahib-e-Qiran[1] Padishah Ghazi Al-Sultan Al-Azam Shahenshah-e-Hind (King of Kings of India) | |||||||||||||

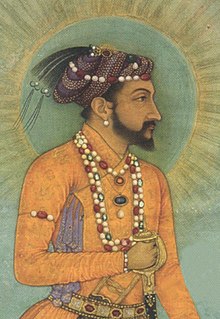

Portrait by Bichitr, c. 1630 | |||||||||||||

| Emperor of Hindustan | |||||||||||||

| Reign | 19 January 1628 – 31 July 1658[2] | ||||||||||||

| Coronation | 14 February 1628[3] | ||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Jahangir I Shahriyar (de facto) | ||||||||||||

| Successor | Aurangzeb | ||||||||||||

| Grand Viziers | |||||||||||||

| Born | Khurram[4] 5 January 1592 Lahore, Lahore Subah, Mughal Empire (present-day Punjab, Pakistan) | ||||||||||||

| Died | 22 January 1666 (aged 74) Muthamman Burj, Red Fort, Agra, Agra Subah, Mughal Empire (present-day Uttar Pradesh, India) | ||||||||||||

| Burial | Taj Mahal, Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India | ||||||||||||

| Wives |

| ||||||||||||

| Issue among others... | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| House | House of Babur | ||||||||||||

| Dynasty | Mughal dynasty | ||||||||||||

| Father | Jahangir I | ||||||||||||

| Mother | Jagat Gosain | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam (Hanafi) | ||||||||||||

| Imperial Seal |  | ||||||||||||

Mirza Shahab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram (5 January 1592 – 22 January 1666), commonly called Shah Jahan I (Persian pronunciation: [ʃɑːh d͡ʒa.ˈhɑːn]; lit. 'King of the World'), also called Shah Jahan the Magnificent,[7][8] was Emperor of Hindustan from 1628 until his deposition in 1658. As the fifth Mughal emperor, his reign marked the zenith of Mughal architectural and cultural achievements.

The third son of Jahangir (r. 1605–1627), Shah Jahan participated in the military campaigns against the Sisodia Rajputs of Mewar and the rebel Lodi nobles of the Deccan. After Jahangir's death in October 1627, Shah Jahan defeated his youngest brother Shahryar Mirza and crowned himself emperor in the Agra Fort. In addition to Shahryar, Shah Jahan executed most of his rival claimants to the throne. He commissioned many monuments, including the Red Fort, Shah Jahan Mosque and the Taj Mahal, where his favorite consort Mumtaz Mahal is entombed. In foreign affairs, Shah Jahan presided over the aggressive campaigns against the Deccan sultanates, the conflicts with the Portuguese, and the wars with the Safavids. He also suppressed several local rebellions and dealt with the devastating Deccan famine of 1630–32.

In September 1657, Shah Jahan was ailing and appointed his eldest son Dara Shikoh as his successor. This nomination led to a succession crisis among his three sons, from which Shah Jahan's third son Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707) emerged victorious and became the sixth emperor, executing all of his surviving brothers, including Crown Prince Dara Shikoh. After Shah Jahan recovered from his illness in July 1658, Aurangzeb imprisoned him in Agra Fort from July 1658 until his death in January 1666.[9] He was laid to rest next to his wife in the Taj Mahal. His reign is known for doing away with the liberal policies initiated by his grandfather Akbar. During Shah Jahan's time, Islamic revivalist movements like the Naqshbandi began to shape Mughal policies.[10]

Early life

Birth and background

He was born on 5 January 1592 in Lahore, present-day Pakistan, as the ninth child and third son of Prince Salim (later known as 'Jahangir' upon his accession) by his wife, Jagat Gosain.[11][12] The name Khurram (Persian: خرم, lit. 'joyous') was chosen for the young prince by his grandfather, Emperor Akbar, with whom the young prince shared a close relationship.[12] Jahangir stated that Akbar was very fond of Khurram and had often told him "There is no comparison between him and your other sons. I consider him my true son."[13]

When Khurram was born, Akbar considering him to be auspicious insisted the prince be raised in his household rather than Salim's and was thus entrusted to the care of Ruqaiya Sultan Begum. Ruqaiya assumed the primary responsibility for raising Khurram[14] and is noted to have raised Khurram affectionately. Jahangir noted in his memoirs that Ruqaiya had loved his son, Khurram, "a thousand times more than if he had been her own [son]."[15]

However, after the death of his grandfather Akbar in 1605, he returned to the care of his mother, Jagat Gosain whom he cared for and loved immensely. Although separated from her at birth, he had become devoted to her and had her addressed as Hazrat in court chronicles.[16][17] On the death of Jagat Gosain in Akbarabad on 8 April 1619, he is recorded to be inconsolable by Jahangir and mourned for 21 days. For these three weeks of the mourning period, he attended no public meetings and subsisted on simple vegetarian meals. His consort Mumtaz Mahal personally supervised the distribution of food to the poor during this period. She led the recitation of the Quran every morning and gave her husband many lessons on the substance of life and death and begged him not to grieve.[18]

Education

As a child, Khurram received a broad education befitting his status as a Mughal prince, which included martial training and exposure to a wide variety of cultural arts, such as poetry and music, most of which was inculcated, according to court chroniclers, by Jahangir. According to his chronicler Qazvini, prince Khurram was only familiar with a few Turki words and showed little interest in the study of the language as a child.[19] Khurram was attracted to Hindi literature since his childhood, and his Hindi letters were mentioned in his father's biography, Tuzuk-e-Jahangiri.[20] In 1605, as Akbar lay on his deathbed, Khurram, who at this point of time was 13,[citation needed] remained by his bedside and refused to move even after his mother tried to retrieve him. Given the politically uncertain times immediately preceding Akbar's death, Khurram was in a fair amount of physical danger from political opponents of his father.[21] He was at last ordered to return to his quarters by the senior women of his grandfather's household, namely Salima Sultan Begum and his grandmother Mariam-uz-Zamani as Akbar's health deteriorated.[22]

Khusrau rebellion

In 1605, his father succeeded to the throne, after crushing a rebellion by Prince Khusrau – Khurram remained distant from court politics and intrigues in the immediate aftermath of that event.[citation needed] Khurram left Ruqaiya's care and returned to his mother's care.[23] As the third son, Khurram did not challenge the two major power blocs of the time, his father's and his half-brother's; thus, he enjoyed the benefits of imperial protection and luxury while being allowed to continue with his education and training. This relatively quiet and stable period of his life allowed Khurram to build his own support base in the Mughal court, which would be useful later on in his life.[24]

Jahangir assigned Khurram to guard the palace and treasury while he went to pursue Khusrau. He was later ordered to bring Mariam-uz-Zamani, his grandmother and Jahangir's harem to him.[25]

During Khusrau's second rebellion, Khurram's informants informed him about Fatehullah, Nuruddin and Muhammad Sharif gathered around 500 men at Khusrau's instigation and lay await for the Emperor. Khurram relayed this information to Jahangir who praised him.[26]

Jahangir had Khurram weighed against gold, silver and other wealth at his mansion at Orta.[27]

Nur Jahan

Due to the long period of tensions between his father and his half-brother, Khusrau Mirza, Khurram began to drift closer to his father, and over time, started to be considered the de facto heir-apparent by court chroniclers. This status was given official sanction when Jahangir granted the sarkar of Hissar-e-Feroza, which had traditionally been the fief of the heir-apparent, to Khurram in 1608.[28] After her marriage to Jahangir in the year 1611, Nur Jahan gradually became an active participant in all decisions made by Jahangir and gained extreme powers in administration, so much so that it was obvious to everyone both inside and outside that most of his decisions were actually hers. Slowly, while Jahangir became more indulgent in wine and opium, she was considered to be the actual power behind the throne. Her near and dear relatives acquired important positions in the Mughal court, termed the Nur Jahan junta by historians. Khurram was in constant conflict with his stepmother, Nur Jahan who favoured her son-in-law Shahryar Mirza for the succession to the Mughal throne over him. In the last years of Jahangir's life, Nur Jahan was in full power, and the emperor had left all the burden of governance on her. She tried to weaken Khurram's position in the Mughal court by sending him on campaigns far in Deccan while ensuring several favours were being bestowed on her son-in-law. Khurram after sensing the danger posed to his status as heir-apparent rebelled against his father in 1622 but did not succeed and eventually lost the favour of his father. Several years before Jahangir's death in 1627, coins began to be struck containing Nur Jahan's name along with Jahangir's name; In fact, there were two prerogatives of sovereignty for the legitimacy of a Muslim monarchy (reading the Khutbah and the other being the right to mint coins). After the death of Jahangir in 1627, a struggle developed between Khurram and his half-brother, Shahryar Mirza for the succession to the Mughal throne. Khurram won the battle of succession and became the fifth Mughal Emperor. Nur Jahan was subsequently deprived of her imperial stature, authority, privileges, honors and economic grants and was put under house arrest on the orders of Khurram and led a quiet and comfortable life till her death.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Shah Jahan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Marriages

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

In 1607, Khurram became engaged to Arjumand Banu Begum (1593–1631), who is also known as Mumtaz Mahal (Persian lit. ' The Exalted One of the Palace'). They were about 14 and 15 when they were engaged, and five years later, got married. The young girl belonged to an illustrious Persian noble family that included Abu'l-Hasan Asaf Khan, who had been serving Mughal emperors since the reign of Akbar. The family's patriarch was Mirza Ghiyas Beg, who was also known by his title I'timād-ud-Daulah or "Pillar of the State". He had been Jahangir's finance minister and his son, Asaf Khan – Arjumand Banu's father – played an important role in the Mughal court, eventually serving as Chief Minister. Her aunt Mehr-un-Nissa later became the Empress Nur Jahan, chief consort of Emperor Jahangir.[29]

The prince would have to wait five years before he was married in 1612 (1021 AH), on a date selected by the court astrologers as most conducive to ensuring a happy marriage. This was an unusually long engagement for the time. However, Shah Jahan first married a Persian Princess (name not known) entitled Kandahari Begum, the daughter of a great-grandson of the great Shah Ismail I of Persia, with whom he had a daughter, his first child.[30]

In 1612, aged 20, Khurram married Mumtaz Mahal, on a date chosen by court astrologers. The marriage was a happy one and Khurram remained devoted to her. They had fourteen children, out of whom seven survived into adulthood.

Though there was genuine love between the two, Arjumand Banu Begum was a politically astute woman and served as a crucial advisor and confidante to her husband.[31] Later on, as empress, Mumtaz Mahal wielded immense power, such as being consulted by her husband in state matters, attending the council (shura or diwan), and being responsible for the imperial seal, which allowed her to review official documents in their final draft. Shah Jahan also gave her the right to issue her own orders (hukums) and make appointments to him. [citation needed]

Mumtaz Mahal died at the young age of 38 (7 June 1631), upon giving birth to Princess Gauhar Ara Begum in the city of Burhanpur, Deccan of a postpartum haemorrhage, which caused considerable blood-loss after painful labor of thirty hours.[32] Contemporary historians note that Princess Jahanara, aged 17, was so distressed by her mother's pain that she started distributing gems to the poor, hoping for divine intervention, and Shah Jahan was noted as being "paralysed by grief" and weeping fits.[33] Her body was temporarily buried in a walled pleasure garden known as Zainabad, originally constructed by Shah Jahan's uncle Prince Daniyal along the Tapti River. Her death had a profound impact on Shah Jahan's personality and inspired the construction of the marvelous Taj Mahal, where she was later reburied.[34]

Khurram had taken other wives, among whom were Kandahari Begum (m. 28 October 1610) and another Persian Princess Izz un-Nisa Begum (m. 2 September 1617), the daughters of Prince Muzaffar Husain Mirza Safawi and Shahnawaz Khan, son of Abdul Rahim Khan-I-Khana, respectively. But according to court chroniclers, these marriages were more out of political consideration, and they enjoyed only the status of being royal wives.[citation needed]

Khurram is also recorded to have married his maternal half-cousin, a Rathore Rajput Princess Kunwari Leelavati Deiji, daughter of Kunwar Sakat/Sagat or Shakti Singh son of Mota Raja Udai Singh and half brother of Raja Sur Singh of Marwar. The marriage took place at Jodhpur when Khurram was in rebellion against his father, emperor Jahangir.[35]

Relationship with Jahanara

After Shah Jahan fell ill in 1658, his daughter Jahanara Begum had a significant influence in the Mughal administration.[36][37] As a result, several accusations of an incestual relationship between Shah Jahan and Jahanara were propagated.[38] Such accusations have been dismissed by modern historians as gossip, as no witness of an incident has been mentioned.[39]

Historian K. S. Lal also dismisses such claims as rumors propagated by courtiers and mullahs. He cites Aurangzeb's confining of Jahanara in the Agra Fort with the Royal prisoner and the talk of the low people magnifying a rumor. [40]

Several contemporary travelers have mentioned such accessions. Francois Bernier, a French physician, mentions rumors of an incestuous relationship being propagated in the Mughal Court.[41] However, Bernier did not mention witnessing such a relationship.[42] Niccolao Manucci, a Venetian traveler, dismisses such accusations by Bernier as gossip and "The talk of the Low People".[38][43]

Early military campaigns

Prince Khurram showed extraordinary military talent. The first occasion for Khurram to test his military prowess was during the Mughal campaign against the Rajput state of Mewar, which had been a hostile force to the Mughals since Akbar's reign.[44]

After a year of a harsh war of attrition, Rana Amar Singh I surrendered conditionally to the Mughal forces and became a vassal state of the Mughal Empire as a result of Mughal expedition of Mewar.[45] In 1615, Khurram presented Kunwar Karan Singh, Amar Singh's heir to Jahangir. Khurram was sent to pay homage to his mother and stepmothers and was later awarded by Jahangir.[46] The same year, his mansab was increased from 12000/6000 to 15000/7000, to equal that his brother Parvez's and was further increased to 20000/10000 in 1616.[47][48]

In 1616, on Khurram's departure to Deccan, Jahangir awarded him the title Shah Sultan Khurram.[49]

In 1617, Khurram was directed to deal with the Lodis in the Deccan to secure the Empire's southern borders and to restore imperial control over the region. On his return 1617 after successes in these campaigns, Khurram performed koronush before Jahangir who called him to jharoka and rose from his seat to embrace him. Jahangir also granting him the title of Shah Jahan (Persian: "King of the World")[50] and raised his military rank to 30000/20000 and allowed him a special throne in his Durbar, an unprecedented honor for a prince.[51] Edward S. Holden writes, "He was flattered by some, envied by others, loved by none."[52]

In 1618, Shah Jahan was given the first copy of Tuzk-e-Jahangiri by his father who considered him "the first of all my sons in everything."[53]

Rebel prince

Inheritance in the Mughal Empire was not determined through primogeniture, but by princely sons competing to achieve military successes and consolidating their power at court. This often led to rebellions and wars of succession. As a result, a complex political climate surrounded the Mughal court in Shah Jahan's formative years. In 1611 his father married Nur Jahan, the widowed daughter of a Persian noble. She rapidly became an important member of Jahangir's court and, together with her brother Asaf Khan, wielded considerable influence. Arjumand was Asaf Khan's daughter and her marriage to Khurram consolidated Nur Jahan and Asaf Khan's positions in court.

Court intrigues, however, including Nur Jahan's decision to have her daughter from her first marriage wed Prince Khurram's youngest brother Shahzada Shahryar and her support for his claim to the throne led to much internal division. Prince Khurram resented the influence Nur Jahan held over his father and was angered at having to play second fiddle to her favourite Shahryar, his half-brother and her son-in-law. When the Persians besieged Kandahar, Nur Jahan was at the helm of the affairs. She ordered Prince Khurram to march for Kandahar, but he refused. As a result of Prince Khurram's refusal to obey Nur Jahan's orders, Kandahar was lost to the Persians after a forty-five-day siege.[54] Prince Khurram feared that in his absence Nur Jahan would attempt to poison his father against him and convince Jahangir to name Shahryar the heir in his place. This fear brought Prince Khurram to rebel against his father rather than fight against the Persians.

In 1622, Prince Khurram raised an army and marched against his father and Nur Jahan.[54] He was defeated at Bilochpur in March 1623. Later he took refuge in Udaipur Mewar with Maharana Karan Singh II. He was first lodged in Delwada Ki Haveli and subsequently shifted to Jagmandir Palace on his request. Prince Khurram exchanged his turban with the Maharana and that turban is still preserved in Pratap Museum, Udaipur (R V Somani 1976). It is believed that the mosaic work of Jagmandir inspired him to use mosaic work in the Taj Mahal of Agra. In November 1623, he found safe asylum in Bengal Subah after he was driven from Agra and the Deccan. He advanced through Midnapur and Burdwan. At Akbarnagar, he defeated and killed the then Subahdar of Bengal, Ibrahim Khan Fath-i-Jang, on 20 April 1624.[55] He entered Dhaka and "all the elephants, horses, and 4,000,000 rupees in specie belonging to the Government were delivered to him". After a short stay he then moved to Patna.[56] His rebellion did not succeed in the end and he was forced to submit unconditionally after he was defeated near Allahabad. Although the prince was forgiven for his errors in 1626, tensions between Nur Jahan and her stepson continued to grow beneath the surface.

Upon the death of Jahangir in 1627, the wazir Asaf Khan, who had long been a quiet partisan of Prince Khurram, acted with unexpected forcefulness and determination to forestall his sister's plans to place Prince Shahryar on the throne. He put Nur Jahan in close confinement. He obtained control of Prince Khurram's three sons who were under her charge. Asaf Khan also managed palace intrigues to ensure Prince Khurram's succession to the throne.[57] Prince Khurram succeeded to the Mughal throne as Abu ud-Muzaffar Shihab ud-Din Mohammad Sahib ud-Quiran ud-Thani Shah Jahan Padshah Ghazi (Urdu: شهاب الدین محمد خرم), or Shah Jahan.[58]

His regnal name is divided into various parts. Shihab ud-Din, meaning "Star of the Faith", Sahib al-Quiran ud-Thani, meaning "Second Lord of the Happy Conjunction of Jupiter and Venus". Shah Jahan, meaning "King of the World", alluding to his pride in his Timurid roots and his ambitions. More epithets showed his secular and religious duties. He was also titled Hazrat Shahenshah ("His Imperial Majesty"), Hazrat-i-Khilafat-Panahi ("His Majesty the Refuge of the Caliphate"), Hazrat Zill-i-Ilahi ("His Majesty the Shadow of God").[59]

His first act as ruler was to execute his chief rivals and imprison his stepmother Nur Jahan. Upon Shah Jahan's orders, several executions took place on 23 January 1628. Those put to death included his brother Shahryar; his nephews Dawar and Garshasp, sons of Shah Jahan's previously executed brother Prince Khusrau; and his cousins Tahmuras and Hoshang, sons of the late Prince Daniyal Mirza.[60][61] This allowed Shah Jahan to rule his empire without contention.

Reign

Evidence from the reign of Shah Jahan states that in 1648 the army consisted of 911,400 infantry, musketeers, and artillery men, and 185,000 Sowars commanded by princes and nobles.

His cultural and political initial steps have been described as a type of the Timurid Renaissance, in which he built historical and political bonds with his Timurid heritage mainly via his numerous unsuccessful military campaigns on his ancestral region of Balkh. In various forms, Shah Jahan appropriated his Timurid background and grafted it onto his imperial legacy.[62]

During his reign the Marwari horse was introduced, becoming Shah Jahan's favorite, and various Mughal cannons were mass-produced in the Jaigarh Fort. Under his rule, the empire became a huge military machine and the nobles and their contingents multiplied almost fourfold, as did the demands for more revenue from their citizens. But due to his measures in the financial and commercial fields, it was a period of general stability – the administration was centralized and court affairs systematized.

The Mughal Empire continued to expand moderately during his reign as his sons commanded large armies on different fronts. India at the time was a rich center of the arts, crafts and architecture, and some of the best of the architects, artisans, craftsmen, painters and writers of the world resided in Shah Jahan's empire. According to economist Angus Maddison, Mughal-era India's share of global gross domestic product (GDP) grew from 22.7% in 1600 to 24.4% in 1700, surpassing China to become the world's largest.[63][64] E. Dewick and Murray Titus, quoting Badshahnama, write that 76 temples in Benares were demolished on Shah Jahan's orders.[65]

Famine of 1630

A famine broke out in 1630–32 in Deccan, Gujarat and Khandesh as a result of three main crop failures.[66] Two million died of starvation, grocers sold dogs' flesh and mixed powdered bones with flour. It is reported that parents ate their own children. Some villages were completely destroyed, their streets filled with human corpses. In response to the devastation, Shah Jahan set up langar (free kitchens) for the victims of the famine.[67]

Successful military campaigns against Deccan Sultanates

In 1632, Shah Jahan captured the fortress at Daulatabad, Maharashtra and imprisoned Husein Shah of the Nizam Shahi Kingdom of Ahmednagar. Golconda submitted in 1635 and then Bijapur in 1636. Shah Jahan appointed Aurangzeb as Viceroy of the Deccan, consisting of Khandesh, Berar, Telangana, and Daulatabad. During his viceroyalty, Aurangzeb conquered Baglana where he defeated defeated Baharji, the Raja,[68][69][70][71] The small Maratha kingdom of Baglana straddled the main route from Surat and the western ports to Burhanpur in the Deccan, and had been subservient to one Muslim ruler or other for centuries. In 1637, however, Shah Jahan decided on complete annexation.[68][72] Baharji, who had commanded the Baglana forces, died soon after the conquest. His son converted to Islam and received the title of Daulatmand Khan.[68][73]

Aurangzeb then defeated Golconda in 1656, and then Bijapur in 1657.[74]

Sikh rebellion led by Guru Hargobind

A rebellion of the Sikhs led by Guru Hargobind took place and, in response, Shah Jahan ordered their destruction. Guru Hargobind defeated the Mughal's army in the Battle of Amritsar, Battle of Kartarpur, Battle of Rohilla, and the Battle of Lahira.

Relations with the Safavid dynasty

Shah Jahan and his sons captured the city of Kandahar in 1638 from the Safavids, prompting the retaliation of the Persians led by their ruler Abbas II of Persia, who recaptured it in 1649. The Mughal armies were unable to recapture it despite repeated sieges during the Mughal–Safavid War.[75] Shah Jahan also expanded the Mughal Empire to the west beyond the Khyber Pass to Ghazna and Kandahar.

Military campaign in Central Asia

Shah Jahan launched an invasion of Central Asia from 1646 to 1647 against the Khanate of Bukhara. With an total army of 75,000, Shah Jahan and his sons Aurangzeb and Murad Bakhsh temporarily occupied the territories of Balkh and Badakhshan. However, they retreated from the fruitless lands and Balkh and Badakhshan returned to Bukharan control.[76]

Relations with the Ottoman Empire

Shah Jahan sent an embassy to the Ottoman court in 1637. Led by Mir Zarif, it reached Sultan Murad IV the following year, while he was encamped in Baghdad. Zarif presented him with fine gifts and a letter which encouraged an alliance against Safavid Persia. The Sultan sent a return embassy led by Arsalan Agha. Shah Jahan received the ambassador in June 1640.[citation needed]

While he was encamped in Baghdad, Murad IV is known to have met ambassadors of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, Mir Zarif and Mir Baraka, who presented 1000 pieces of finely embroidered cloth and even armor. Murad IV gave them the finest weapons, saddles and Kaftans and ordered his forces to accompany the Mughals to the port of Basra, where they set sail to Thatta and finally Surat.[77] They exchanged lavish presents, but Shah Jahan was displeased with Sultan Murad's return letter, the tone of which he found discourteous. Sultan Murad's successor, Sultan Ibrahim, sent Shah Jahan another letter encouraging him to wage war against the Persians, but there is no record of a reply.[77]

War with Portuguese

Shah Jahan gave orders in 1631 to Qasim Khan, the Mughal viceroy of Bengal, to drive out the Portuguese from their trading post at Port Hoogly. The post was heavily armed with cannons, battleships, fortified walls, and other instruments of war.[78] The Portuguese were accused of trafficking by high Mughal officials and due to commercial competition the Mughal-controlled port of Saptagram began to slump. Shah Jahan was particularly outraged by the activities of Jesuits in that region, notably when they were accused of abducting peasants. On 25 September 1632, the Mughal Army raised imperial banners and gained control over the Bandel region, and the garrison was punished.[79] On 23 December 1635, Shah Jahan issued a farman ordering the Agra Church to be demolished. The Church was occupied by the Portuguese Jesuits. However the Emperor allowed the Jesuits to conduct their religious ceremonies in privacy. He also banned the Jesuits in preaching their religion and making converts from both Hindus and Muslims.[80][81]Though in the decree, he also granted 777 bighas of rent-free land to the Augustinian Fathers and the Christian community in Bandel, currently in West Bengal, shaping its Portuguese heritage for times to come.[82]

Revolts against Shah Jahan

The Kolis of Gujarat rebelled against the rule of Shah Jahan. In 1622, Shah Jahan sent Raja Vikramjit, the Governor of Gujarat, to subdue the Kolis of Ahmedabad.[83] Between 1632 and 1635, four viceroys were appointed in an effort to manage the Koli's activities. The Kolis of Kankrej in North Gujarat committed excesses and the Jam of Nawanagar refused to pay tribute to Shah Jahan. Soon, Ázam Khán was appointed in an effort to subdue the Kolis and bring order to the province. Ázam Khán marched against Koli rebels. When Ázam Khán reached Sidhpur, the local merchants complained bitterly of the outrages of one Kánji, a Chunvalia Koli, who had been especially daring in plundering merchandise and committing highway robberies. Ázam Khán, anxious to start with a show of vigour before proceeding to Áhmedábád, marched against Kánji, who fled to the village of Bhádar near Kheralu, sixty miles north-east of Áhmedábád. Ázam Khán pursued him so hotly that Kánji surrendered, handed over his plunder and guaranteed that he would not only cease to commit robberies but also pay an annual tribute of Rupees 10,000. Ázam Khán then built two fortified posts in the Koli's territory, naming one Ázamábád after himself, and the other Khalílábád after his son. Additionally, he forced the surrender of the Jam of Nawanagar.[84] The next viceroy, Ísa Tarkhán, carried out financial reforms. In 1644, the Mughal prince Aurangzeb was appointed as the viceroy, who then proceeded to become engaged in religious disputes, such as the destruction of a Jain temple in Ahmedabad. Due to these disputes, he was replaced by Shaista Khan who failed to subdue Kolis. Subsequently, prince Murad Bakhsh was appointed as the viceroy in 1654. He restored order and defeated the Koli rebels.[85]

Illness and death

When Shah Jahan became ill in 1658, Dara Shikoh (Mumtaz Mahal's eldest son) assumed the role of regent in his father's stead, which swiftly incurred the animosity of his brothers.[86] Upon learning of his assumption of the regency, his younger brothers, Shuja, Viceroy of Bengal, and Murad Baksh, Viceroy of Gujarat, declared their independence and marched upon Agra in order to claim their riches. Aurangzeb, the third son, gathered a well-trained army and became its chief commander. He faced Dara's army near Agra and defeated him during the Battle of Samugarh.[87] Although Shah Jahan fully recovered from his illness, Aurangzeb declared him incompetent to rule and put him under house arrest in Agra Fort.

Jahanara Begum Sahib, Mumtaz Mahal's eldest surviving daughter, voluntarily shared his 8-year confinement and nursed him in his dotage. In January 1666, Shah Jahan fell ill. Confined to bed, he became progressively weaker until, on 22 January, he commended the ladies of the imperial court, particularly his consort of later years Akbarabadi Mahal, to the care of Jahanara. After reciting the Kal'ma (Laa ilaaha ill allah) and verses from the Quran, Shah Jahan died, aged 74.

Shah Jahan's chaplain Sayyid Muhammad Qanauji and Kazi Qurban of Agra came to the fort, moved his body to a nearby hall, washed it, enshrouded it, and put it in a coffin of sandalwood.[31]

Princess Jahanara had planned a state funeral which was to include a procession with Shah Jahan's body carried by eminent nobles followed by the notable citizens of Agra and officials scattering coins for the poor and needy. Aurangzeb refused to accommodate such ostentation. The body was taken to the Taj Mahal and was interred there next to the body of his beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal.[88]

Contributions to architecture

Shah Jahan left behind a grand legacy of structures constructed during his reign. He was one of the greatest patrons of Mughal architecture.[89] His reign ushered in the golden age of Mughal architecture.[90] His most famous building was the Taj Mahal, which he built out of love for his wife, the empress Mumtaz Mahal. His relationship with Mumtaz Mahal has been heavily adapted into Indian art, literature and cinema. Shah Jahan personally owned the royal treasury, and several precious stones such as the Kohinoor.

Its structure was drawn with great care and architects from all over the world were called for this purpose. The building took twenty years to complete and was constructed from white marble underlaid with brick. Upon his death, his son Aurangzeb had him interred in it next to Mumtaz Mahal. Among his other constructions are the Red Fort also called the Delhi Fort or Lal Qila in Urdu, large sections of Agra Fort, the Jama Masjid, the Wazir Khan Mosque, the Moti Masjid, the Shalimar Gardens, sections of the Lahore Fort, the Mahabat Khan Mosque in Peshawar, the Mini Qutub Minar[91] in Hastsal, the Jahangir mausoleum – his father's tomb, the construction of which was overseen by his stepmother Nur Jahan and the Shahjahan Mosque. He also had the Peacock Throne, Takht e Taus, made to celebrate his rule. Shah Jahan also placed profound verses of the Quran on his masterpieces of architecture.[92]

The Shah Jahan Mosque in Thatta, Sindh province of Pakistan (100 km / 60 miles from Karachi) was built during the reign of Shah Jahan in 1647. The mosque is built with red bricks with blue coloured glaze tiles probably imported from another Sindh's town of Hala. The mosque has overall 93 domes and it is the world's largest mosque having such a number of domes. It has been built keeping acoustics in mind. A person speaking inside one end of the dome can be heard at the other end when the speech exceeds 100 decibels. It has been on the tentative UNESCO World Heritage list since 1993.[93]

-

The elegant Naulakha Pavilion at the Lahore Fort was built during the reign of Shah Jahan.

-

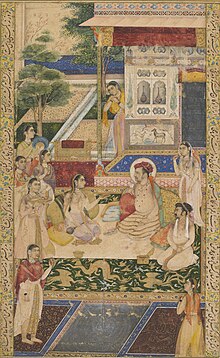

Shah Jahan and the Mughal Army return after attending a congregation in the Jama Masjid, Delhi.

-

Lahore's Wazir Khan Mosque is considered to be the most ornate Mughal-era mosque.[94]

Coins

Shah Jahan continued striking coins in three metals i.e. gold (mohur), silver (rupee) and copper (dam). His pre-accession coins bear the name Khurram.

-

Gold Mohur from Akbarabad (Agra)

-

Silver rupee coin of Shah Jahan, from Patna.

-

Copper Dam from Daryakot mint

-

Silver Rupee from Multan

-

Silver Rupee coin of Shah Jahan, struck in Patna mint, 1135 AH, 1635 AD, Regnal Year 8.

| Styles of Shah Jahan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Shahanshah |

| Spoken style | His Imperial Majesty |

| Alternative style | Alam Pana |

Issue

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

| Name | Mother | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parhez Banu Begum | Kandahari Begum | 21 August 1611 – 1675 |

Shah Jahan's first child born to his first wife, Kandahari Begum. Parhez Banu was her mother's only child and died unmarried. | |

| Hur-ul-Nisa Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 30 March 1613 – 5 June 1616 |

The first of fourteen children born to Shah Jahan's second wife, Mumtaz Mahal. She died of smallpox at the age of 3.[95] | |

| Jahanara Begum Padshah Begum |

Mumtaz Mahal |

|

23 March 1614 – 16 September 1681 |

Shah Jahan's favourite and most influential daughter. Jahanara became the First Lady (Padshah Begum) of the Mughal Empire after her mother's death, despite the fact that her father had three other consorts. She died unmarried. |

| Dara Shikoh Padshahzada-i-Buzurg Martaba, Jalal ul-Kadir, Sultan Muhammad Dara Shikoh, Shah-i-Buland Iqbal |

Mumtaz Mahal |

|

20 March 1615 – 30 August 1659 |

The eldest son and heir-apparent. He was favoured as a successor by his father, Shah Jahan, and his elder sister, Princess Jahanara Begum, but was defeated and later killed by his younger brother, Prince Muhiuddin (later the Emperor Aurangzeb), in a bitter struggle for the imperial throne. He married and had issue. |

| Shah Shuja | Mumtaz Mahal |

|

23 June 1616 – 7 February 1661 |

He survived in the war of succession. He married and had issue. |

| Roshanara Begum Padshah Begum |

Mumtaz Mahal |

|

3 September 1617 – 11 September 1671 |

She was the most influential of Shah Jahan's daughters after Jahanara Begum and sided with Aurangzeb during the war of succession. She died unmarried. |

| Aurangzeb Mughal emperor |

Mumtaz Mahal |

|

3 November 1618 – 3 March 1707 |

Succeeded his father as the sixth Mughal emperor after emerging victorious in the war of succession that took place after Shah Jahan's illness in 1657. |

| Jahan Afroz | Izz-un-Nissa | 25 June 1619 – March 1621 |

The only child of Shah Jahan's third wife, Izz-un-Nissa (titled Akbarabadi Mahal). Jahan Afroz died at the age of one year and nine months.[96] | |

| Izad Bakhsh | Mumtaz Mahal | 18 December 1619 – February/March 1621[97] |

Died in infancy. | |

| Surayya Banu Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 10 June 1621 – 28 April 1628[97] |

Died of smallpox at the age of 7.[95] | |

| Unnamed son | Mumtaz Mahal | 1622 | Died soon after birth.[97] | |

| Murad Bakhsh | Mumtaz Mahal |

|

8 October 1624 – 14 December 1661 |

He was killed in 1661 as per Aurangzeb's orders.[95] He married and had issue. |

| Lutf Allah | Mumtaz Mahal | 4 November 1626 – 13 May 1628[97] |

Died at the age of one and a half years.[95] | |

| Daulat Afza | Mumtaz Mahal | 8 May 1628 – 13 May 1629[98] |

Died in infancy. | |

| Husnara Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 23 April 1629 – 1630[97] |

Died in infancy. | |

| Gauhara Begum | Mumtaz Mahal | 17 June 1631 – 1706 |

Mumtaz Mahal died while giving birth to her on 17 June 1631 in Burhanpur. She died unmarried. |

Inscriptions

The inscription from Makrana, Nagaur District, dating back to 1651 AD, mentions Mirza Ali Baig, who was likely a local governor under Shah Jahan's rule.[100] It describes a notice he posted on a step-well, prohibiting low-caste individuals from using the well alongside higher-caste people.[101]

See also

- Shah Jahan II

- Shah Jahan III

- Wine cup of Shah Jahan

- Shahjehan, 1946 Indian film about the emperor

References

Notes

- ^ "Lords of the Auspicious Conjunction: The Ottoman, Safavid, and Mughal Empires and the Islamic Ecumene". Shah Jahan. LSE International Studies. Cambridge University Press. 18 June 2020. pp. 167–213. doi:10.1017/9781108867948.007. ISBN 978-1-108-49121-1.

- ^ Shujauddin, Mohammad; Shujauddik, Razia (1967). The Life and Times of Noor Jahan. Lahore: Caravan Book House. p. 121. OCLC 638031657.

- ^ Necipoğlu, Gülru, ed. (1994). Muqarnas : an annual on Islamic art and architecture. Vol. 11. Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill. p. 143. ISBN 978-90-04-10070-1.

- ^ Fenech, Louis E. (2014). "The Evolution of the Sikh Community". In Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

Jahangir's son, ponkua, better known as the emperor Shah Jahan the Architect

- ^ Singh, Pashaura; Fenech, Louis E., eds. (2014). "Index". The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 649. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

Shah Jahan, Emperor Shahabuddin Muhammad Khurram

- ^ Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoglu, Gulru (2017). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 897. ISBN 978-1-119-06857-0.

- ^ Gabrielle Festing (2008). When Kings Rode to Delhi. Lancer Publishers. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-9796174-9-2.

- ^ Stanley Lane-Poole (January 2008). History of India: Mediaeval India from the Mohammedan Conquest to the Reign of Akbar the Great, Volume 4. Cosimo. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-60520-496-3.

- ^ Illustrated dictionary of the Muslim world. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish Reference. 2011. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-7614-7929-1.

- ^ Richards 1993, Shah Jahan, pp. 121–122.

- ^ "Shah Jahan". Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 October 2023.

- ^ a b Findly 1993, p. 125

- ^ Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Thackston, W. M. Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 0-19-512718-8.

- ^ Eraly 2000, p. 299

- ^ Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Thackston, W. M. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 0-19-512718-8.

- ^ Kamboh, Muhammad Saleh. Amal I Salih.

During her stay at Fatehpur, the mother of Shah Jahan, Hazrat Bilqis Makani, a resident of Agra became ill. The treatment did not work. Finally, on 4th Jamadi-ul-Awal, she died and according to her will, she was buried at Dehra Bagh, near Noor Manzil.

- ^ Perston, Diana; Perston, Micheal. A Teardrop on the Cheek of Time: The Story of the Taj Mahal.

Although removed from his mother at birth, Shah Jahan had become devoted to her.

- ^ Lal, Muni (1986). Shah Jahan. Vikas Publishing House. p. 52.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena (1932). History Of Shahjahan Of Dihli 1932. Indian Press Limited.

- ^ Saiyada Asad Alī (2000). Influence of Islam on Hindi Literature. Idarah-i-Adabiyat-Delli. p. 48.

- ^ Prasad 1930, p. 189 "During his grandfather's last illness, he [Khurram] refused to leave the bedside surrounded by his enemies. Neither the advice of his father nor the entreaties of his mother could prevail on him to prefer the safety of his life to his last duty to the father."

- ^ Nicoll 2009, p. 49

- ^ Faruqui, Munis D. (2012). The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-107-02217-1.

- ^ Nicoll 2009, p. 56

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 61. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 84. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 81. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Prasad 1930, p. 190 "Khusrau conspired, rebelled, and lost the favour of his father ... Of all the sons of Jahangir, Khurram was marked out to be the heir-apparent and successor ... In 1608 the assignment of the sarkar of Hissar Firoz to him proclaimed to the world that he was intended for the throne."

- ^ Nicoll 2009, p. 66

- ^ Eraly 2000, p. 300

- ^ a b Eraly 2000, p. 379

- ^ Kumar, Anant (January–June 2014). "Monument of Love or Symbol of Maternal Death: The Story Behind the Taj Mahal". Case Reports in Women's Health. 1: 4–7. doi:10.1016/j.crwh.2014.07.001. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Nicoll 2009, p. 177

- ^ "The Taj Mahal Story". www.tajmahal.gov.in. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ The Mertiyo Rathors of Merta, Rajasthan. Vol. II. p. 45.

- ^ Koul, Ashish (January 2022). "Whom can a Muslim Woman Represent? Begum Jahanara Shah Nawaz and the politics of party building in late colonial India". Modern Asian Studies. 56 (1): 96–141. doi:10.1017/S0026749X20000578. ISSN 0026-749X. S2CID 233690931.

- ^ Bano, Shadab (2013). "Piety and Pricess Jahanara's Role in the Public Domain". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 74: 245–250. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44158822.

- ^ a b Banerjee, Rita (7 July 2021), "Women in India: The "Sati" and the Harem", India in Early Modern English Travel Writings, Brill, pp. 173–208, ISBN 978-90-04-44826-1, retrieved 12 February 2024

- ^ Banerjee, Rita (7 July 2021), "Women in India: The "Sati" and the Harem", India in Early Modern English Travel Writings, Brill, pp. 173–208, ISBN 978-90-04-44826-1, retrieved 12 February 2024

- ^ Lal, Kishori Saran, ed. (1988), "The Charge of Incest", The Mughal Harem, Adithya Prakashan, pp. 93–94

- ^ Constable, Archibald, ed. (1916), "Begum Saheb", Travels in Mogul India, Oxford University Press, p. 11

- ^ Manzar, Nishat (31 March 2023), "Looking Through European Eyes: Mughal State and Religious Freedom as Gleaned from The European Travellers' Accounts of the Seventeenth Century", Islam in India, London: Routledge, pp. 121–132, doi:10.4324/9781003400202-9, ISBN 978-1-003-40020-2, retrieved 12 February 2024

- ^ Irvine, William, ed. (1907), "Begum Saheb", Storia Do Mogor Vol 1, Oxford University press, pp. 216–217

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 154. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Prasad 1930, p. 239 "Constant skirmishes were thinning the Rajput ranks ... [Amar Singh] offered to recognize Mughal supremacy ... Jahangir gladly and unreservedly accepted the terms."

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 116. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 175. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 192. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 201. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Middleton, John (2015). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. p. 451. ISBN 978-1-317-45158-7.

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 228-29. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ Holden, Edward S. (2004) [First published 1895]. Mughal Emperors of Hindustan (1398–1707). New Delhi, India: Asian Educational Service. p. 257. ISBN 978-81-206-1883-1.

- ^ Emperor, Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama. Freer Gallery of Art, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Oxford University Press. pp. 271. ISBN 9780195127188.

- ^ a b Satish Chandra (2007). History of Medieval India: 800–1700. Orient BlackSwan. ISBN 978-8125032267. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ Muazzam Hussain Khan (2012). "Ibrahim Khan Fath-i-Jang". In Sirajul Islam; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. OL 30677644M. Retrieved 29 December 2024.

- ^ Hossain, Syud (1909). Echoes from Old Dacca. Edinburgh Press. p. 6.

- ^ Richards 1993, p. 117

- ^ Nicoll 2009, p. 157

- ^ ʻInāyat Khān, approximately 1627-1670 or 1671 (1990). The Shah Jahan nama of 'Inayat Khan : an abridged history of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan, compiled by his royal librarian : the nineteenth-century manuscript translation of A.R. Fuller (British Library, add. 30,777). Internet Archive. Delhi ; New York : Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-562489-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Elliot, H. M. (1867–1877). The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. Vol. VI. London: Trübner and Co.

- ^ Findly 1993, pp. 275–282, 284

- ^ Ohlander, Erik; Curry, John, eds. (2012). Sufism and Society: Arrangements of the Mystical in the Muslim World, 1200–1800. Routledge. p. 141. ISBN 9781138789357.

- ^ Maddison, Angus (2006). The World Economy Volumes 1–2. Development Center of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. p. 639. doi:10.1787/456125276116. ISBN 9264022619.

- ^ Matthews, Chris (5 October 2014). "The 5 most dominant economic empires of all time". Fortune. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ Titus, Murray T; Dewick, E.C. (1979). Indian Islam. Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 24. ISBN 978-8170690962.

- ^ Ó Gráda, Cormac (March 2007). "Making Famine History". Journal of Economic Literature. 45 (1): 5–38. doi:10.1257/jel.45.1.5. hdl:10197/492. JSTOR 27646746. S2CID 54763671.

Well-known famines associated with back-to-back harvest failures include ... the Deccan famine of 1630–32

- ^ Mahajan, Vidya Dhar (1971) [First published in 1961]. Mughal Rule in India (10th ed.). Delhi: S. Chand. pp. 148–149. OCLC 182638309.

- ^ a b c Richards 1993.

- ^ Maharashtra State Gazetteers: Nasik. Director of Government Printing, Stationery and Publications, Maharashtra State. 1975. p. 87.

- ^ Quddusi, Mohd Ilyas (2002). Khandesh Under the Mughals, 1601-1724 A.D.: Mainly Based on Persian Sources. Islamic Wonders Bureau. p. 40. ISBN 978-81-87763-21-5.

- ^ Faruqui, Munis D. (27 August 2012). The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719. Cambridge University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-139-53675-2.

- ^ Syed, Anees Jahan (1977). Aurangzeb in Mǔntakhab-ǎl Lubab̄ [Muntakhab Allubab, Engl., Ausz.] By Anees Jahan Syed. Somaiya Publications. p. 21.

- ^ Quddusi, Mohd Ilyas (2002). Khandesh Under the Mughals, 1601-1724 A.D.: Mainly Based on Persian Sources. Islamic Wonders Bureau. ISBN 978-81-87763-21-5.

- ^ Sen 2013, pp. 170–171

- ^ Sen 2013, pp. 169–170

- ^ Hada, Ranvijay Singh (18 August 2020). "Balkh Campaign: An Indian Army in Central Asia". PeepulTree.

- ^ a b Farooqi, Naimur Rahman (1989). Mughal-Ottoman Relations: A Study of Political & Diplomatic Relations Between Mughal India and the Ottoman Empire, 1556–1748. Idarah-i Adabiyat-i Delli. pp. 26–30. OCLC 20894584.

- ^ Ikram, S. M. (1964). Muslim Civilization in India. Columbia University Press. pp. 175–188. ISBN 978-0231025805 – via Frances W. Pritchett.

- ^ Duiker, William J.; Spielvogel, Jackson J. (2006). World History: From 1500. Cengage Learning. pp. 431, 475. ISBN 978-0495050544.

- ^ Sharma, Ram, ed. (1962), "Shah Jahan", The Religious policy of the Mughal Emperors, Asian publishing house, pp. 104–105

- ^ "Asnad.org Digital Persian Archives: Detail view document 356". asnad.org.

- ^ "Why Bengal owes much of its food and language to the Portuguese". The Indian Express. 5 July 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ Behera, Maguni Charan (2019). Tribal Studies in India: Perspectives of History, Archaeology and Culture. New Delhi, India: Springer Nature. p. 46. ISBN 978-9813290266.

- ^ Campbell, James Macnabb (1896). "Chapter III. Mughal Viceroys. (A.D. 1573–1758)". History of Gujarát. Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency. Vol. I(II). The Government Central Press. p. 279.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Ashburner, Bhagvánlál Indraji (1839–1888) John Whaley Watson (1838–1889) Jervoise Athelstane Baines (1847–1925) L. R. "History of Gujarát". pp. 278–283. Retrieved 16 October 2022 – via Project Gutenberg.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Gonzalez, Valerie (2016). Aesthetic Hybridity in Mughal Painting, 1526–1658. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1317184874.

- ^ Richards 1993, p. 158

- ^ ASI, India. "Taj Mahal". asi.nic.in. Archeological Survey of India. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Asher 2003, p. 169

- ^ Mehta, Jaswant Lal (1984) [First published 1981]. Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India. Vol. II (2nd ed.). Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 978-8120710153. OCLC 1008395679.

- ^ "A Qutub Minar that not many knew even existed". The Times of India. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ "Callingraphy". www.tajmahal.gov.in. Retrieved 18 March 2024.

- ^ Shah Jahan Mosque UNESCO World Heritage Centre Retrieved 10 February 2011

- ^ Dani, A. H. (2003). "The Architecture of the Mughal Empire (North-Western Regions)" (PDF). In Adle, Chahryar; Habib, Irfan (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. V. UNESCO. p. 524. ISBN 978-9231038761.

- ^ a b c d Moosvi, Shireen (2008). People, Taxation, and Trade in Mughal India. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0195693157.

- ^ Jahangir (1999). The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated by Thackston, W. M. Oxford University Press. p. 362. ISBN 0195127188.

[March 1621 – March 1622] Shah-Shuja escaped the brink of death, and another son born of Shahnawaz Khan's daughter [Izz un-Nisa Begum] in Burhanpur died.

- ^ a b c d e Sarker, Kobita (2007). Shah Jahan and his paradise on earth : the story of Shah Jahan's creations in Agra and Shahjahanabad in the golden days of the Mughals. Kolkata: K.P. Bagchi & Co. p. 40. ISBN 978-8170743002.

- ^ Begley, W. E.; Desai, Z.A., eds. (1989). Taj Mahal: The Illumined Tomb: An Anthology of Seventeenth-Century Mughal and European Documentary Sources. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-295-96944-2.

- ^ Epigraphia Indica. Arabic and Persian supplement (in continuation of the series Epigraphia Indo-Moslemica). Public Resource. Archaeological Survey of India. 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Archaeology progress report of the A.S.I., Western Circle. Central Archeological Library. p. 40.

Under management of Mirza Ali Baig. As the date A.H. 1061 is equivalent to A.D. 1650, the 25th year must refer to Shah Jahan's reign, Mirza Ali Baig must have been his local governor.

- ^ A. Ghosh, (Director General of Archaeology in India) (22 December 1965). Indian Archaeology 1962-63, A Review. Government of India Press, Faridabad. p. 60.

INSCRIPTIONS OF THE MUGHALS, DISTRICTS JAIPUR, NAGAUR AND TONK.—Of the inscriptions of Shah Jahan, the one from Makrana, District Nagaur, records a notice put up on a step-well in А.Н. 1061 (A.D. 1651) by Mirza Ali Baig prohibiting the low-caste people from drawing water from the well along with the people of higher caste.

Bibliography

- Asher, Catherine Ella Blanshard (2003) [1992]. Architecture of Mughal India. The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. I: 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 368. ISBN 978-0521267281.

- Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the Peacock Throne: The Saga of the Great Mughals. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0141001432.

- Findly, Ellison Banks (1993). Nur Jahan: Empress of Mughal India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195360608.

- Koch, Ebba (2006). The Complete Taj Mahal: And the Riverfront Gardens of Agra. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0500342091.

- Nicoll, Fergus (2009). Shah Jahan: The Rise and Fall of the Mughal Emperor. London: Haus. ISBN 978-1906598181.

- Prasad, Beni (1930) [1922]. History of Jahangir (2nd ed.). Allahabad: The Indian Press.

- Richards, John F. (1993). The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge History of India. Vol. V. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521566032.

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. ISBN 978-9380607344.

![Lahore's Wazir Khan Mosque is considered to be the most ornate Mughal-era mosque.[94]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/28/Wazir_khan_mosque_entry.jpg/120px-Wazir_khan_mosque_entry.jpg)